As we enjoy our national Presidents' Day holiday, it’s a timely notion to recollect the special relationship that young George Washington forged in Allegany County, Maryland, as a young adventurer, soldier, and even as our first president.

We are fortunate to have our own “George Washington,” as one of America’s respected historical actors, John Koopman III, visits Allegany County, the Mountain Side of Maryland, annually in September for the annual Heritage Days Festival and the Wills Creek Muster in The Passages of the Western Potomac Heritage Area.

However, the “real” George Washington was only 16 years old when he first laid eyes on Allegany County on a 1748 survey mission to map the lands of Lord Fairfax and establish the source of the Potomac River - a spring at the head of the North Branch still marked as the location of the Fairfax Stone.

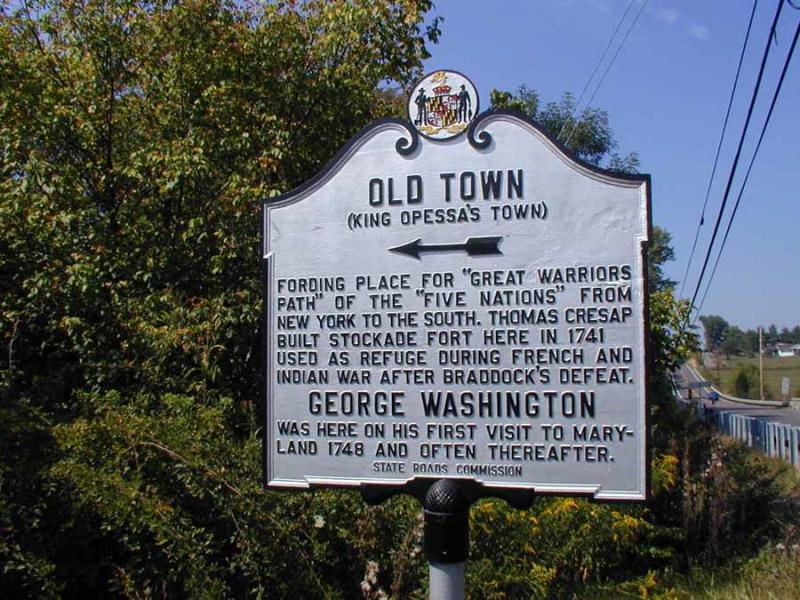

In his colorful daily account of the mission, Washington famously described his experience at the fortified home and trading post of one Col. Thomas Cresap, a renowned pioneer in Western Maryland history. Trapped by a March rainstorm and flash flood, Washington and his companion were surprised when 30 native tribesmen arrived with a scalp and proceeded to “party down,” replete with whisky, playing music from a deerskin drum and dancing well into the night. These were the first American Indians Washington encountered.

Col. Cresap was known among the natives as “Big Spoon” for his hospitality, most likely a wise strategy given his business opportunity in the fur trade, located directly on the Warrior Trail that traveled south from New York through Oldtown, Maryland.

Between 1753 and 1758, Washington traveled frequently to the confluence of Wills Creek and North Branch to a site that would eventually host British Fort Cumberland and become the city of Cumberland.

These were much less happy visits for Washington, now in his early 20s. War clouds had gathered around conflicts between France and England over the fur trade long the Ohio River basin. Allegany County was suddenly the Western Frontier of the British Empire, the border in a trade war against an alliance of French army units and native tribes headquartered around the future location of Pittsburgh.

Washington saw little military success in these campaigns but established a reputation of a daring soldier of strong character. An unsuccessful trip to Venango in 1753 to convince the French to withdraw (not a very practical hope, to say the least) resulted in a popular book in England written by Washington about his harrowing adventure. He was accompanied by guide Christopher Gist who would become his constant companion here in the mountains during the French and Indian War.

Things got worse in the two years that followed. A Virginia militia foray toward Fort Duquesne in 1754 was a rough lesson for the future Revolutionary War hero. He ambushed a French party at Jumonville Glen in nearby Pennsylvania, inadvertently allowing a tribal grudge killing of a French officer of noble birth. The enraged French North American commander marched immediately to the makeshift fort Washington built near the ambush and routed the Virginia militia. In signing the Fort Necessity surrender document, written in French, Washington admitted wrongdoing. The dust up that followed made him a controversial subject in Parliament and led to the formal declaration of the French and Indian War.

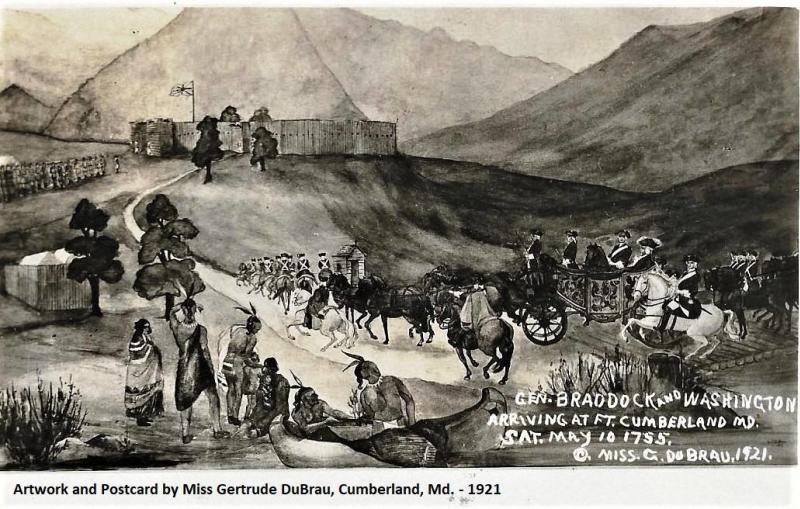

Washington repaired to Mount Vernon, stinging from the events of 1754, but was recruited to return to the service of the British military as an aide du camp for British General Edward Braddock and 2,000 regulars who built Fort Cumberland in the Spring of 1755.

Photo compliments of Al Feldstein.

Braddock sorely underestimated the challenges of both the terrain and the cleverness of his savvy opponents. Ignoring the advice of the seasoned Washington, the General staged a massive road building campaign to drive the French from Fort Duquesne, only to suffer a disastrous ambush just several miles short of this objective. Braddock was mortally wounded; a large number of his officers were killed, and it fell to the 24-year-old Washington to quell the rout and guide the surviving army back to Fort Cumberland. Historians often surmise that the lessons of Braddock’s March created a template in Washington’s military theory that would win the American Revolution two decades later.

President George Washington would return to Allegany County one more time in 1794 in a historic event, to put down the Whiskey Rebellion. Reviewing his troops on the parade ground of the abandoned Fort Cumberland, he became the only U.S. president ever to directly lead troops in the field.

On President’s Day we’re reminded that George Washington slept in many places that are keen to claim his fame, but his time in Allegany County was a formative event – one that changed the course of American history in the years that followed.

MEET THE GUEST BLOGGER!

Dave Williams, Cumberland, MD

Dave Williams is the president of the Allegany County Historical Society and administers the Western Maryland History Facebook Page.